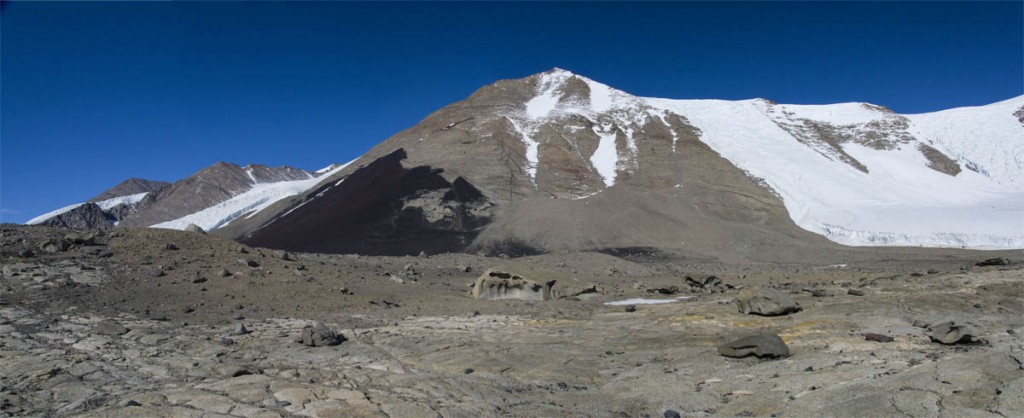

The word “awesome” has taken on a casual meaning, approximating something like, “Super cool!” or “Hey, that’s great!” But there were many times in Antarctica I was confronted by something awesome in the original sense of the word, as in awe-inspiring: difficult to grasp in its immensity and power. Even if you learn the scientific explanation, there’s something unfathomable about a large expanse of bright orange and red ice spilling from the end of the steep walls of a glacier that towers overhead. It’s one of those moments where I’d just stand there for a minute thinking, “I’m in Antarctica. I’m really in Antarctica.” That’s how I felt when I stood at the bottom of Blood Falls, at the toe of the Taylor Glacier in the Dry Valleys, overlooking the west lobe of Lake Bonney.

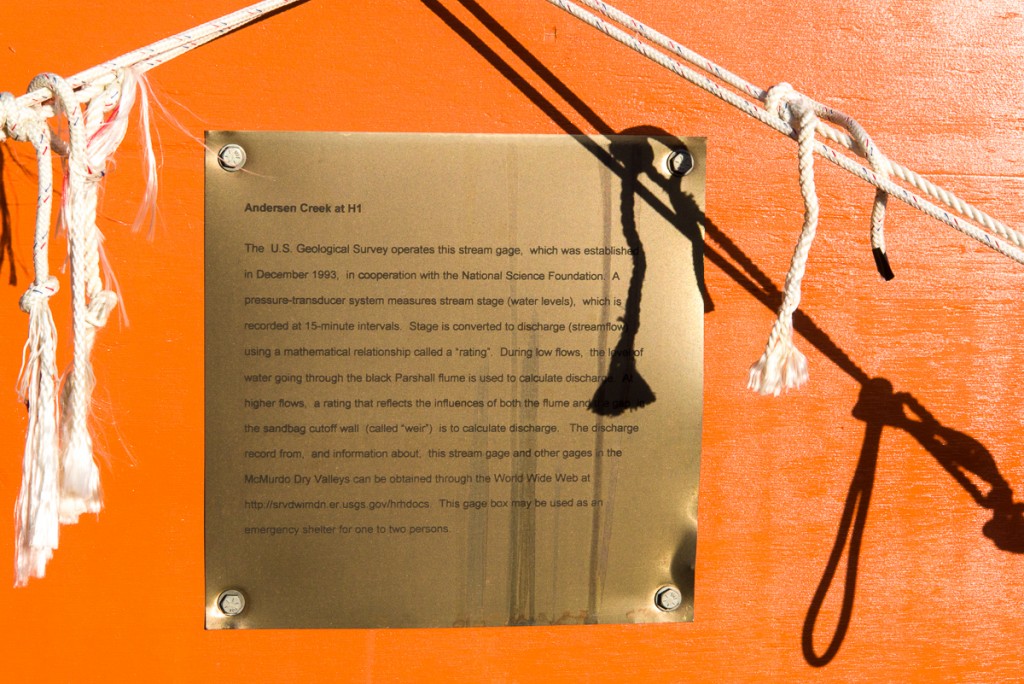

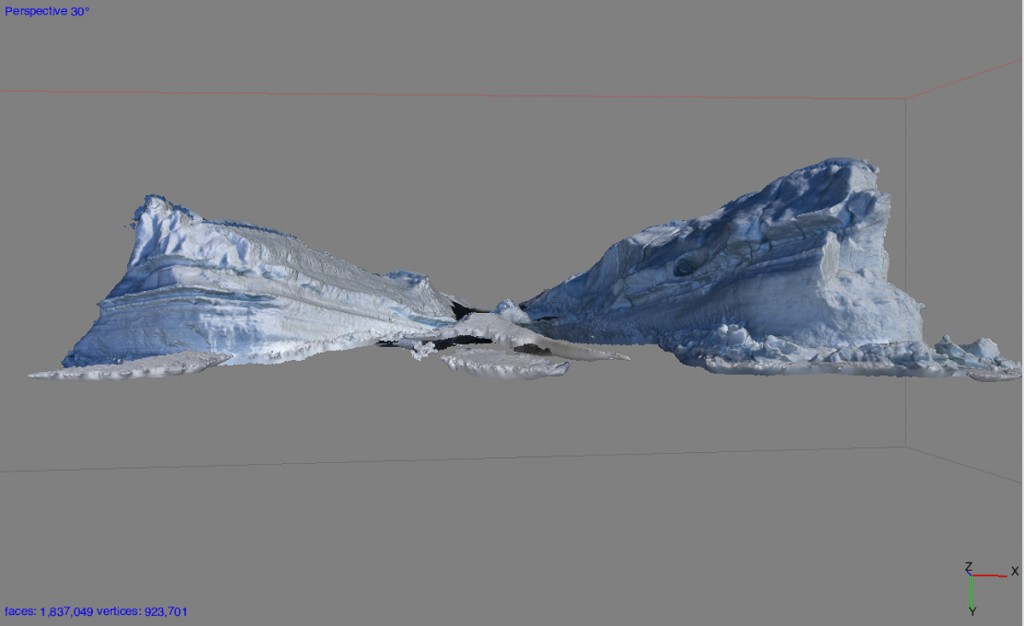

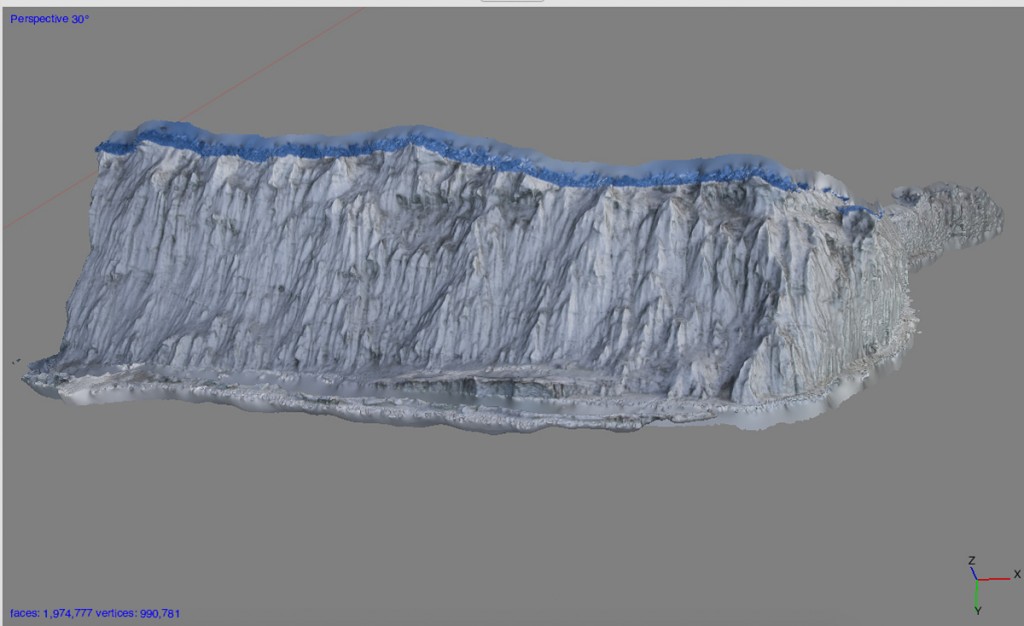

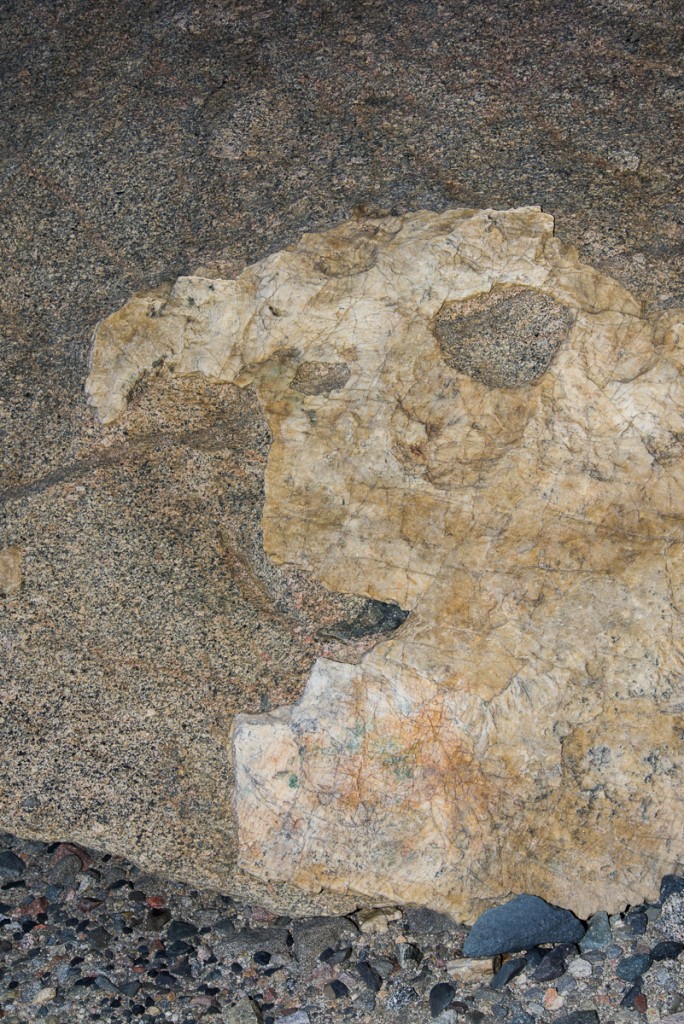

In those I’m-in-Antarctica moments I felt how privileged I was to even be standing there. Since my Antarctic Artists and Writers Program project involved photographing ice formations to recreate in 3D I was among the fortunate few granted a permit to walk around it, not to mention a helicopter ride to the site. Blood Falls is among the highly protected zones of Antarctica because it is both a rare natural phenomenon and harbors delicate mineral deposits, which in turn harbor unusual microbes, all of which one must take care not to trample. National Geographic’s Blood Falls web page offers a good overview of where the minerals and and their colors come from, and the scientific significance of the site. In brief, the iron oxide salts percolate up into the glacier from a hypersaline lake (i.e. super-concentrated salty water) trapped beneath it from geological processes occurring over a period between two and five million years ago. When the iron salts hit the air, they oxygenate and turn red and orange. This is a dynamic process, and I’m told that the depth of the colors varies from year to year.

National Geographic goes on to explain that scientists from a variety of disciplines are interested in the microbes who live in the unusually harsh conditions of these deposits: glaciologists (who study glaciers), limnologists (who study lakes), microbiologists (who study microbes) and astrobiologists (who speculate about the presence of life on other planets). As a group, the microbes fall into the broader category of extremophiles because they “are able to withstand and even thrive in extremely harsh environments.” The extremophiles (I like to think of them as the X-philes) of Blood Falls manage the trick of converting sulfur and iron compounds into energy under freezing conditions. Hence the interest on the part of astrobiologists, since this may be the closest Earth can come to approximating conditions on a freezing planet.

I visited Blood Falls with mountaineer Forrest McCarthy, a veteran of about 20 seasons “on the ice” in the US Antarctic Program. We flew in a helicopter and were joined by Mike Jackson, the National Science Foundation science representative on station for that period. Since Mike’s trip was spur of the moment due to their being room in the helo, he had not obtained a permit. Even an NSF administrator isn’t allowed to walk all the way to the falls without one, so he stayed on a nearby trail overlooking the site, while Forrest and I waded across the shallow but wide melt waters of the Taylor Glacier at the edge of Lake Bonney, which was ankle deep in some places. I had changed into hiking boots instead of bunny boots, so I splashed through the freezing water as fast as I could, hoping my boots were as waterproof as advertised. (They did reasonably well. Lowa boots, in case you’re wondering, from REI. They’re the only ones that come in true narrow widths, so I didn’t have much choice. But they turned out to be great boots.) This was my first view of Bonney, and I knew it was a frozen lake, but I didn’t realize the edges would be swiftly moving water. Or that streams of water would be spilling off the top of the glacier in little waterfalls. I’d never seen a glacier do that before; it seems to be a particularly Dry Valleys phenomenon, where the glaciers are basically grounded rather than actively moving out to sea. (I’ve posted a 13-second video to YouTube.) It was a cold and windy, but sunny day, with a brilliant blue sky.

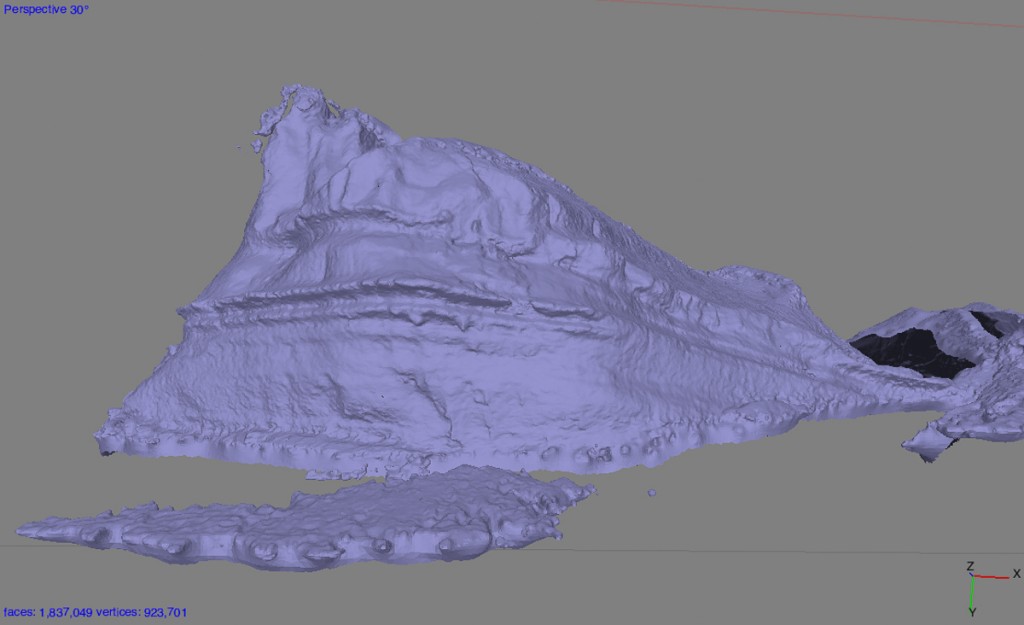

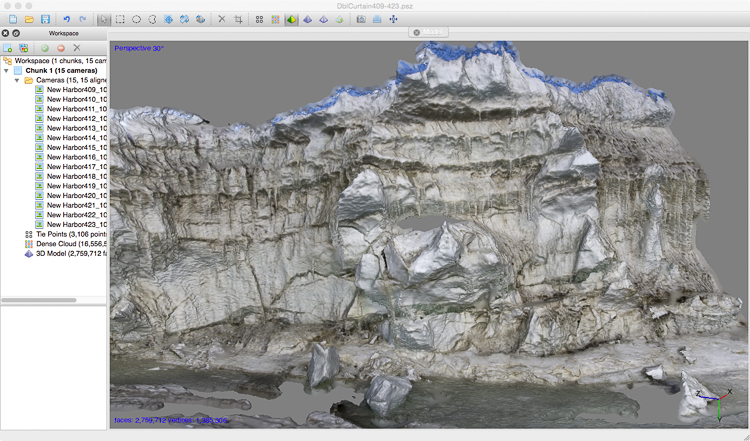

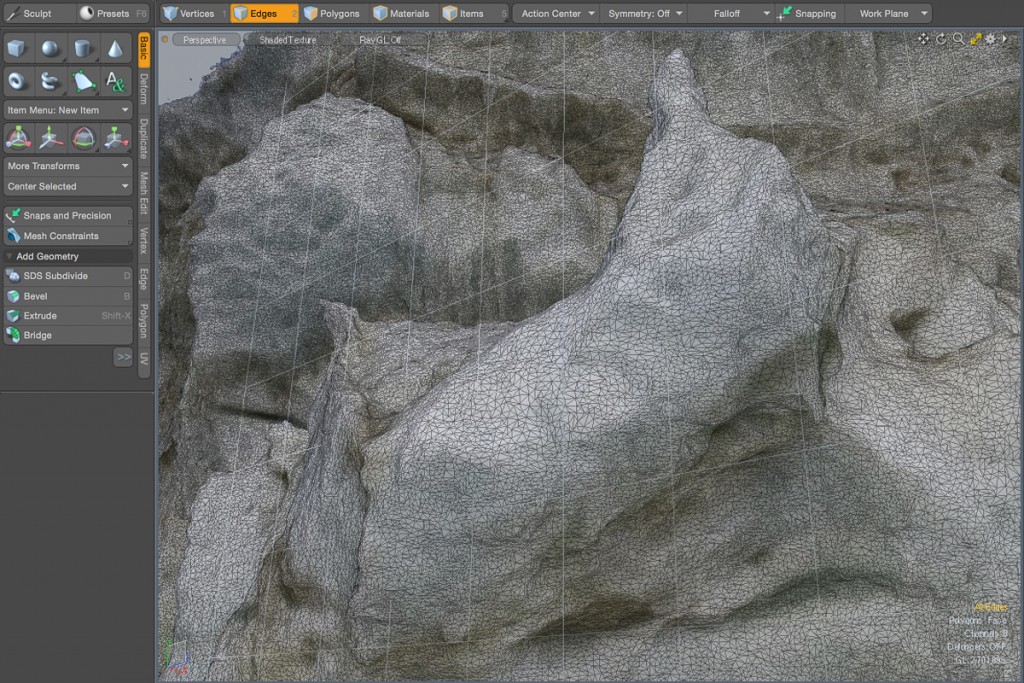

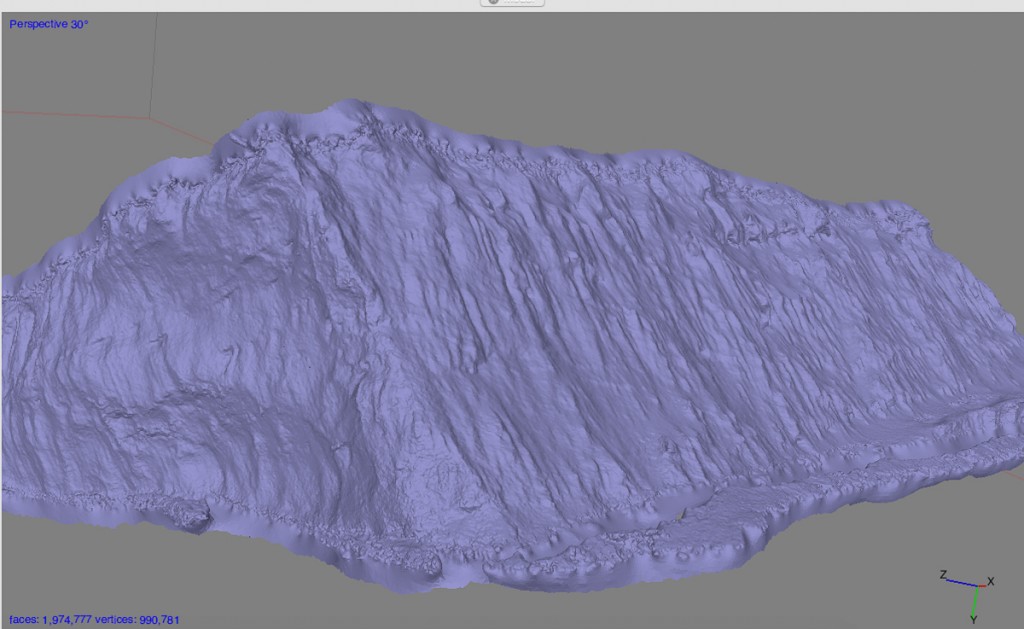

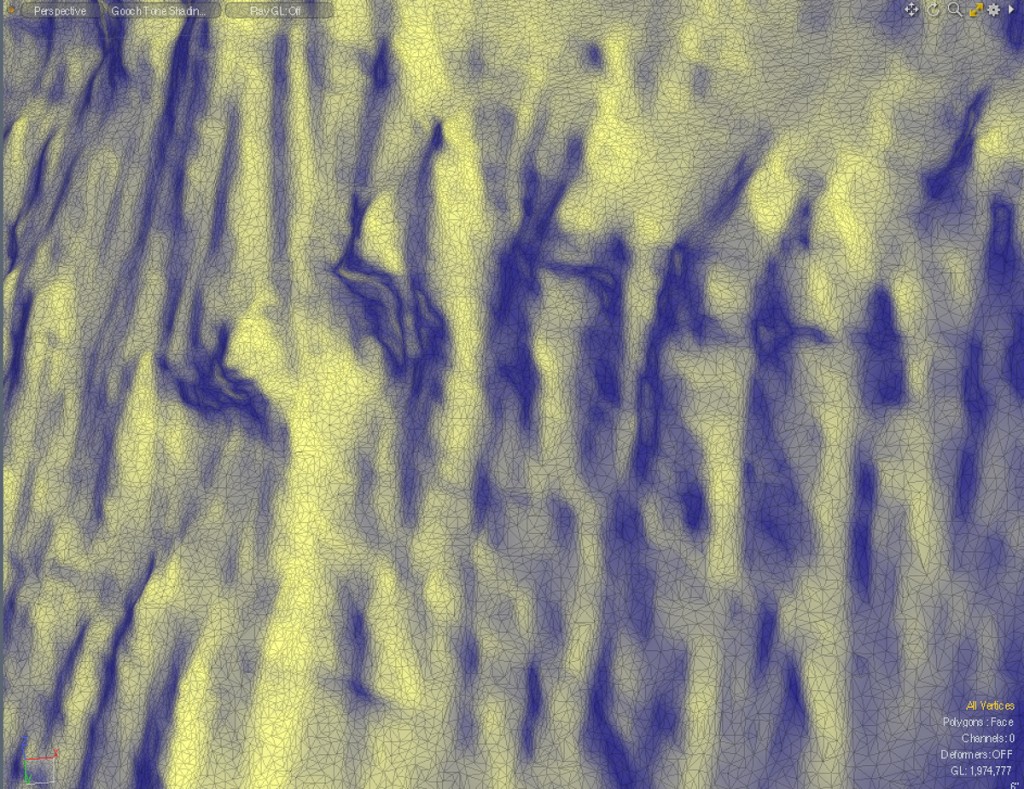

If all goes well, the photos I took during my walk-around can be processed into a 3D file after I return home to recreate this special place as a sculptural form.