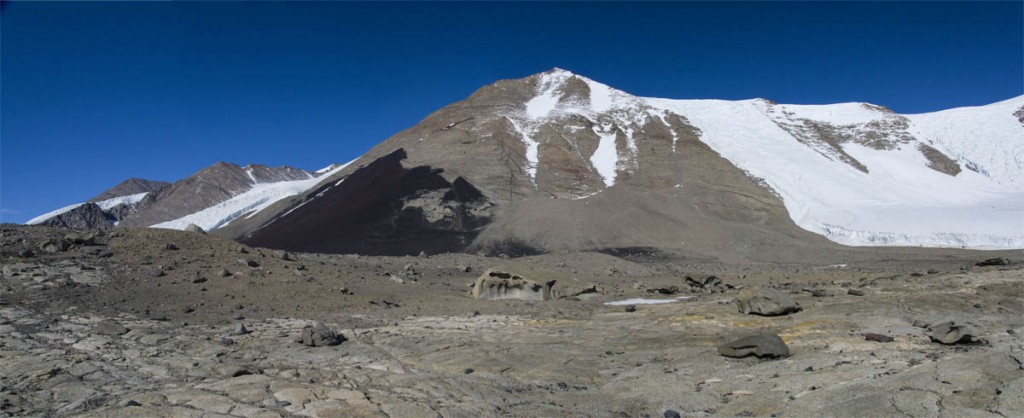

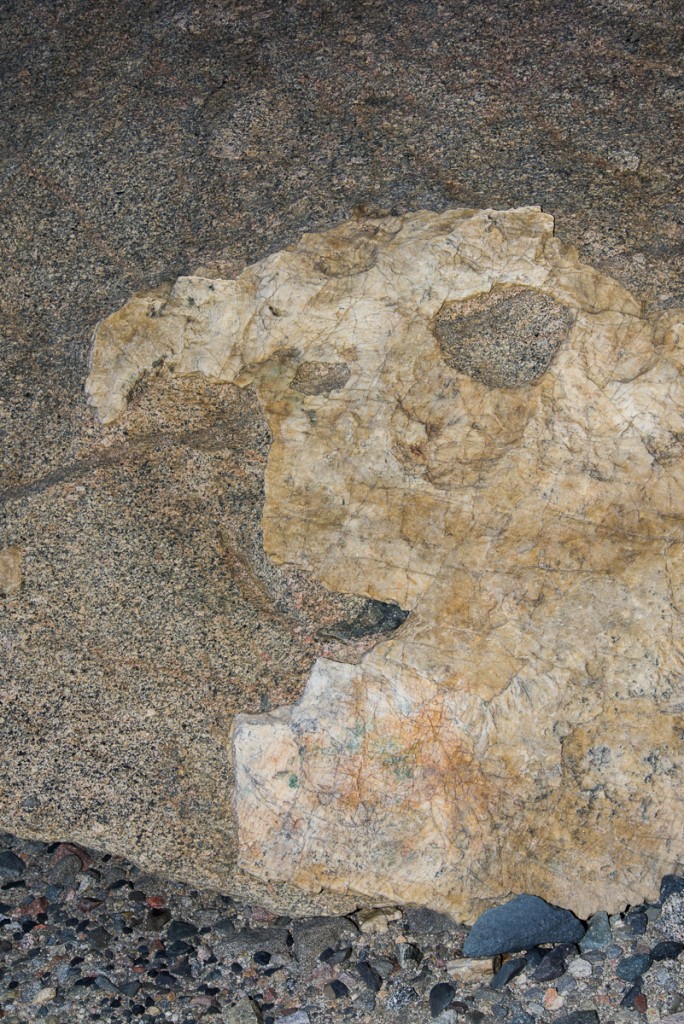

I’ve finished two sculptures made from 3D scans of the Antarctic landscape so far. This latest one is of a ventifact — wind-eroded boulder — that I photographed in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, a trip I recounted in an earlier blog post. I call it the “Bird” Ventifact because from certain angles, it looks like a giant beaked bird with a crest.

In addition to its lively, birdlike presence, part of what attracted me to this form was its concavities and holes, worn by the abrasive action of volcanic gravel carried by fierce Antarctic winds. If a successful sculpture is judged by how it transforms as one walks around it and takes it in from different vantage points, this ventifact certainly works as sculpture. By capturing it in 3D, I’ve “brought it home” for others to experience as an object and not just as a series of flat photographs. Looking at one side hardly predicts what you’ll find on other sides:

In order to capture the complexity of the form, with all its undercuts and hollows, I chose 3D printing over CNC routing, because the router bit only moves up and down in one direction, and does not tilt to get other angles. 3D printing, by contrast, is additive, and builds the form in layers, preventing the undercuts from collapsing during the printing process with temporary supports that can be broken off once the print is finished. Since the 3D printers that I have access to only have a capacity of about 8 x 8 x 11 inches, and my finished sculpture is 16 x 29.25 x 29.25 inches, I had to print it in sections, epoxy it together, and smooth the joints between the pieces before painting it. However, I was able to assemble the 25-odd pieces into a seamless whole. I’ve made this short video of the process. Watch it full screen and see it come together: