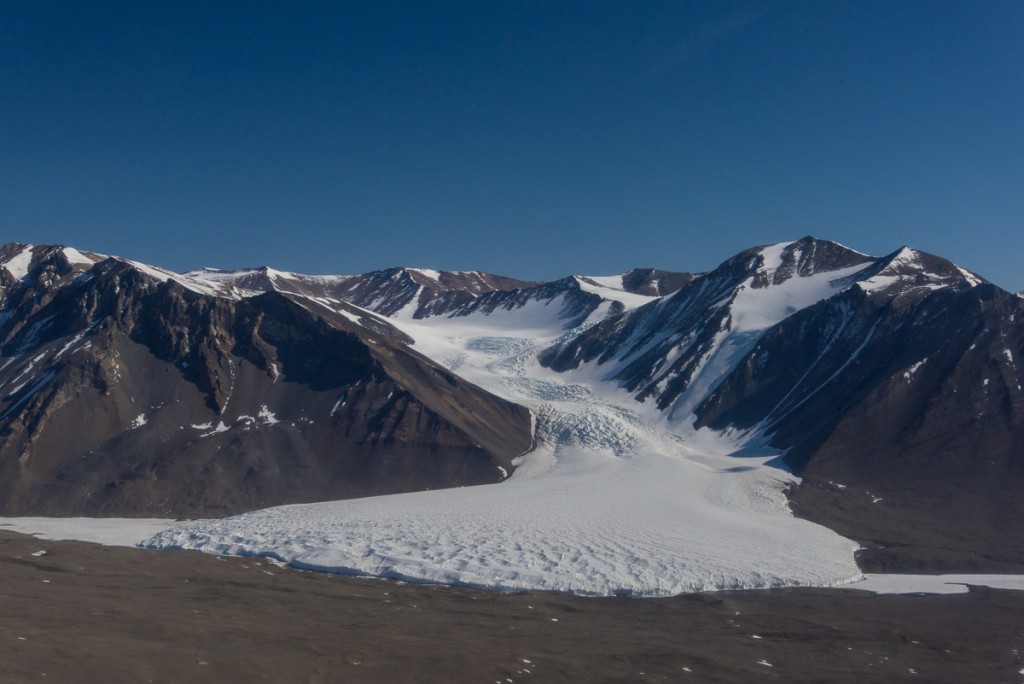

The evening of December 18th, I shook the snow off my tent from the snowstorm earlier that day and spent my first night at the Lake Hoare field camp. Though the dense fog and gray skies lingered long after the snow stopped, camp manager Rae had checked the forecast and said the skies were expected to clear overnight. Sure enough, in the morning we awoke to bright sunshine. I set out on a day hike with Renee, Rae’s assistant at Lake Hoare, to cross over the Canada Glacier and visit the eastern side, which faces Lake Fryxell. The Canada Glacier snakes down from Mt. McLennan, which is about 1,600 meters (5,250 feet) high on the north side of the Taylor Valley. The Lake Hoare camp is nestled beside the western side of the glacier, a tall wall of ice with a relatively smooth and rounded profile reminding me of an adobe house. In the course of walking over it and visiting the other side, I would see that the other side of the glacier looked very different.

Renee is an avid hiker who runs a backcountry lodge at Glacier National Park in Montana during the summer. Before we left, she told me, “I always hike with poles,” and offered to let me use one of hers. In all my years of hiking I had never had used walking sticks or poles; they’d struck me as just another thing to carry. But I figured this was not familiar terrain and if as strong a hiker as Renee relied on them, I’d follow her lead.

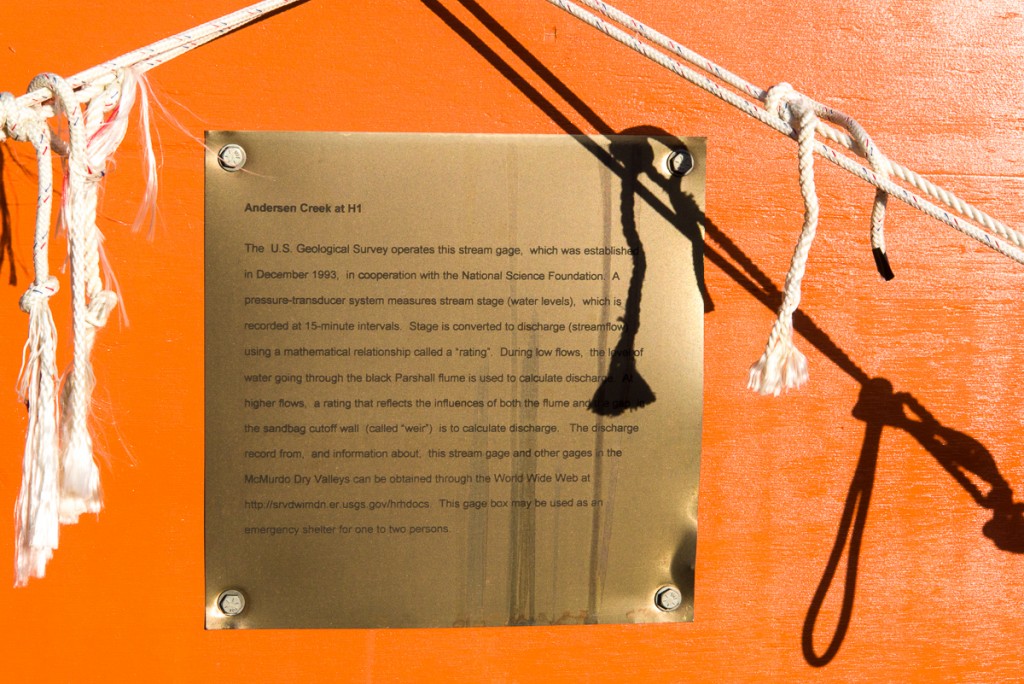

We started up the steep rocky moraine beside the Canada Glacier with the stream ecology team, who were planning to take water samples at various locations. Beside the glacier are piles of large and medium sized rocks and the Andersen Creek, fed by meltwater that comes off the glacier, but it was still so cold and shady in that area that the stream sampling team was having trouble finding thawed meltwater to collect. When we came to an area where the top of the glacier flattened out, we parted ways as they headed for another of the sampling spots. Renee and I put crampons on our boots and headed toward the ice falls, a slope where gravity had creased the glacier and separated it into rows of irregular boulder-sized chunks of blue ice. To the right of the falls, an enormous tongue-shaped section of the glacier clings to a steep face of Mt. McLennan.

Once we were on top of the glacier, I quickly discovered why climbing poles aren’t, um, pointless. The layer of about four inches of snow from the day before lay on top of the glacier, covering areas of thin ice where your foot could punch through into a hollow spot that could be anywhere from a few inches to a couple of feet deep. Underneath could be rocks or small melt pools. This made traversing the area more challenging than usual, when the hazards are more visible. As she walked, Renee rapidly jabbed at the ice ahead with her pole. If the pole punched a hole in the ice, then she’d pause and continue probing until she found a solid spot before taking the next step. I followed suit. Here is a detail of the ice falls, taken with the assistance of a telephoto lens:

After photographing the falls, we continued over the top of the glacier, carefully poking the surface with our poles to avoid the gaps until we stepped off the glacier onto the rocks and gravel on the other side. We looked for tracks where the stream ecology researchers had walked before, but couldn’t always find them, so we had to pick our way carefully, especially when we got close to the edge where the glacier tapered off onto the gravel-covered hill. To the south, there were thin clouds in the sky and the previous day’s snowfall gave the opposite hillside the texture of a tapestry:

Looking toward Lake Hoare while standing on top of the glacier you can take in its scale. We had walked up from the right:

Our next destination, Lake Fryxell, lay ahead to the east. We were up high enough to see the ice-covered summit of the Mt. Erebus volcano in the haze across McMurdo Sound about 13 miles away. After crossing the glacier to the gravel hill on the other side, we ate lunch in a sheltered spot, then headed downhill towards the Lake Fryxell field camp. Our plan was to get in the ATV that stays on the sea ice during the research season and double back across the lake ice to have a closer look at the Fryxell side of the Canada Glacier.

In order to protect the ecology of the streams which run off the Canada Glacier into Lake Fryxell, approximately one square kilometer of the hillside adjoining the glacier and the lake shore has been designated an Antarctic Specially Protected Area (ASPA). Although it looks like just more of the same rocks and gravel you can see for miles in every direction, its relatively sheltered location and the meltwater coming off the glacier makes this tract one of the best places to find life in the polar desert, especially bryophytes (e.g. mosses) and algae. The tiny plants are freeze-dried most of the year, but come briefly to life during the austral summer. To enter one of five ASPAs in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, you must be issued a permit by a national authority, which for the U.S. is the National Science Foundation. I obtained a permit to enter the Blood Falls ASPA but not the Canada Glacier one. The NSF staffer who issues the permits assured me I would be able to get close enough to the glacier from the lake to photograph it and that there was no reason for me to enter the protected site. When I got there, I could see her reasoning. That portion of the glacier isn’t even particularly interesting from a visual standpoint:

Hiking across the gravel to Lake Fryxell we encountered the first of two mummified seals. I made a tentative ID of the one below as a crabeater seal, based on its teeth. The three types of seals found in this part of Antarctica — leopard seals, Weddell seals and crabeaters — all have different shaped teeth.

The next seal we encountered was easily identified as a leopard seal, because due to the freezing temperatures and the lack of organisms such as bacteria and insects, it still had its fur, even though, according to the people at Lake Hoare, it had died there about three years ago. Leopard seals are ferocious predators — when I asked Sam Bowser if his dive team ever saw them at New Harbor, he responded, “No! And I wouldn’t want to.” Leopard seals could attack the divers. Weddell seals, which the divers often do see, are essentially harmless and non-intimidating, even though they weigh over 1,000 lbs. But even a young leopard seal that had drawn its last breath a few years ago looked somewhat sinister with it’s long powerful jaw.

Eventually, we reached the Lake Fryxell Jamesway hut. Nobody was staying at the field camp, though a team of carpenters were expected to return shortly to resume work building a new hut on the site, of the same design as the one at Lake Hoare. When they’re done, the Jamesway will be dismantled, and these photos will be documents of a vanished era. The Lake Bonney Jamesway will be replaced next. There’s something cool and retro about the Jamesways, especially the quirky improvisations and embellishments added over the years as teams of researchers have come and gone, but whatever the boxy Lake Hoare hut lacks in character it is way more functional and comfortable.

After eating a snack in the hut, we headed for the ATV, which was parked on the thick, permanently frozen layer of ice that covers Lake Fryxell. This time of year, the margin of the lake melts, and is a few feet deep. So how do the limnologists (lake scientists) get onto the ice? The ingenious solution, arrived at with Rae’s input, was to have an aluminum rowboat rigged up so that at either end a loop of rope was attached to the boat. Through those loops runs a very long loop of yellow rope, which is threaded through two pulleys, one set up on shore and one on the ice. Get in the boat, pull the yellow rope hand over hand and the boat travels across the water and glides up onto the ice. It kind of reminded me of the old rope tows at ski areas in the 1960s and ’70s.

Once on the lake ice, we walked to the ATV, pulled out the pan underneath it protecting the ice in case oil dripped from the engine (every effort is made to not have any alien materials enter the environment), and made sure the tires weren’t frozen to the ice. Renee got it started, I straddled the back part of the seat behind her, and off we went.

Renee drove cautiously, taking care to not drive too close to cracks around the periphery that might indicate unstable ice, and slowing down when crossing rough areas, which we encountered increasingly as we approached the glacier. I was grateful that she took her time and I wasn’t being bounced around on the narrow back part of the seat. Later on, when we were back at the hut, I told her that I’d appreciated her restraint. She burst out laughing and said, “Oh good! I was thinking, ‘She must think I’m such a wimp!'”

In the distance, Renee waits at the ATV for me to finish photographing the glacier. There were some raised areas of ice at that end, left behind when the rest of the lake ice surface ablated (vaporized). There is nothing as irregular as the ice structures on Lake Hoare, but driving over and around them made for a bumpy ride in places.

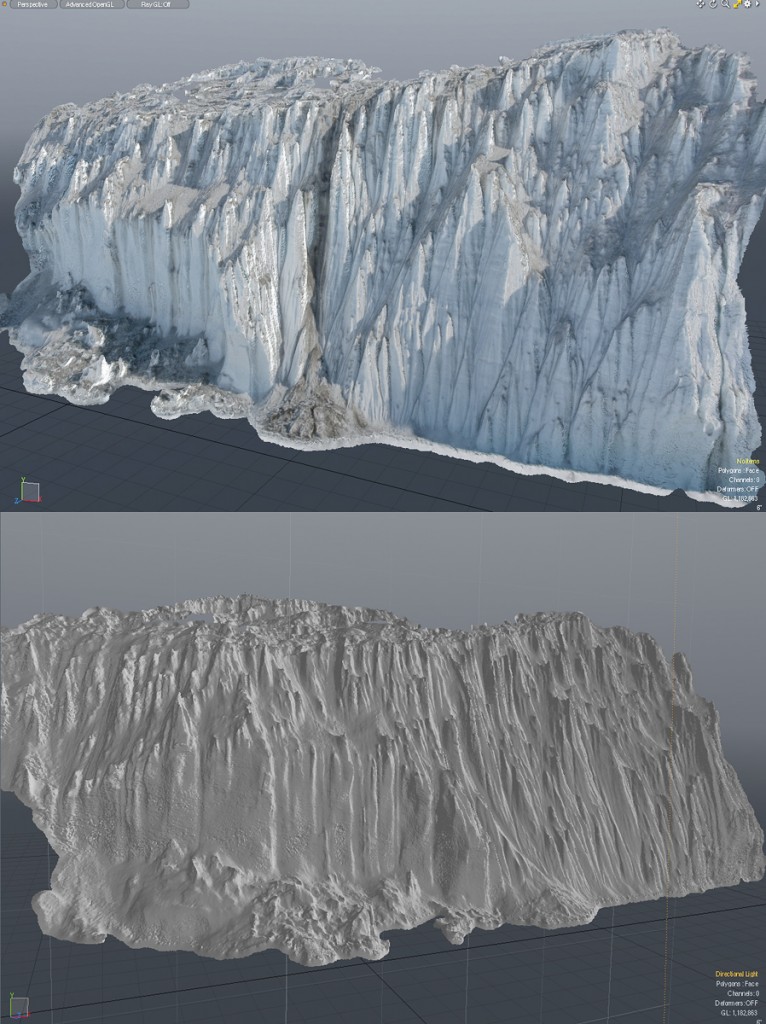

The Lake Fryxell face of the Canada Glacier looks completely different than the Lake Hoare side. For one thing, at its tallest, it’s about twice as high — around 20 meters. That’s because the land slopes beneath it and the surface of Lake Fryxell is actually about 55 meters lower in elevation than that of Lake Hoare. If you look at the second photo from the top of this post, taken from a helicopter, you can see the slope. I am guessing that it’s this downhill gravitational pull as well as the directions of prevailing winds and sunlight that make it look so different — spiky and Gothic with narrow pointy-topped spires, as opposed to the rounded contours on the west-facing side, which get the warmer afternoon and evening sun.

Renee waited patiently while I shot some 300 photos of the glacier side. That’s way more photos than I usually took at a site, because I wanted to see if I could produce a 3D capture (i.e. scan) of the complex surface, and since I hadn’t had much experience tackling something that is both that immense and that detailed, I wasn’t sure how many different angles I would need. So I decided to err on the side of “more than enough.” Eventually some of these 3D captures will be produced as sculpture. (Read more about the process.) Recently I processed one section that I shot that day. It took the software about 18 hours to calculate the relative distances between points to produce a model of the section below, and another few hours for it to generate a polygon mesh, but I’m really pleased — and relieved — with the results. Below is one of the source photos, followed by screenshots of the model.

After returning the ATV to its parking place, the hike back to Lake Hoare was more challenging than the hike out had been, due to gusty winds that had kicked up. The rowboat tilted to one side while Renee was pulling it to shore and I immediately shifted my weight onto the gunwale to stabilize it, to her great relief (amazing how those instincts kicked in from the long ago days of taking out sailboats at Camp Whippoorwill, when I was 13 ). The sky started to cloud, and on the top of the glacier, the previous day’s snowfall was swirling around, making me even happier to have a pole in my hand to prod the ice in front of me, and also glad that I’d stopped to photograph the ice falls in the morning. Then we walked down the moraine to camp.

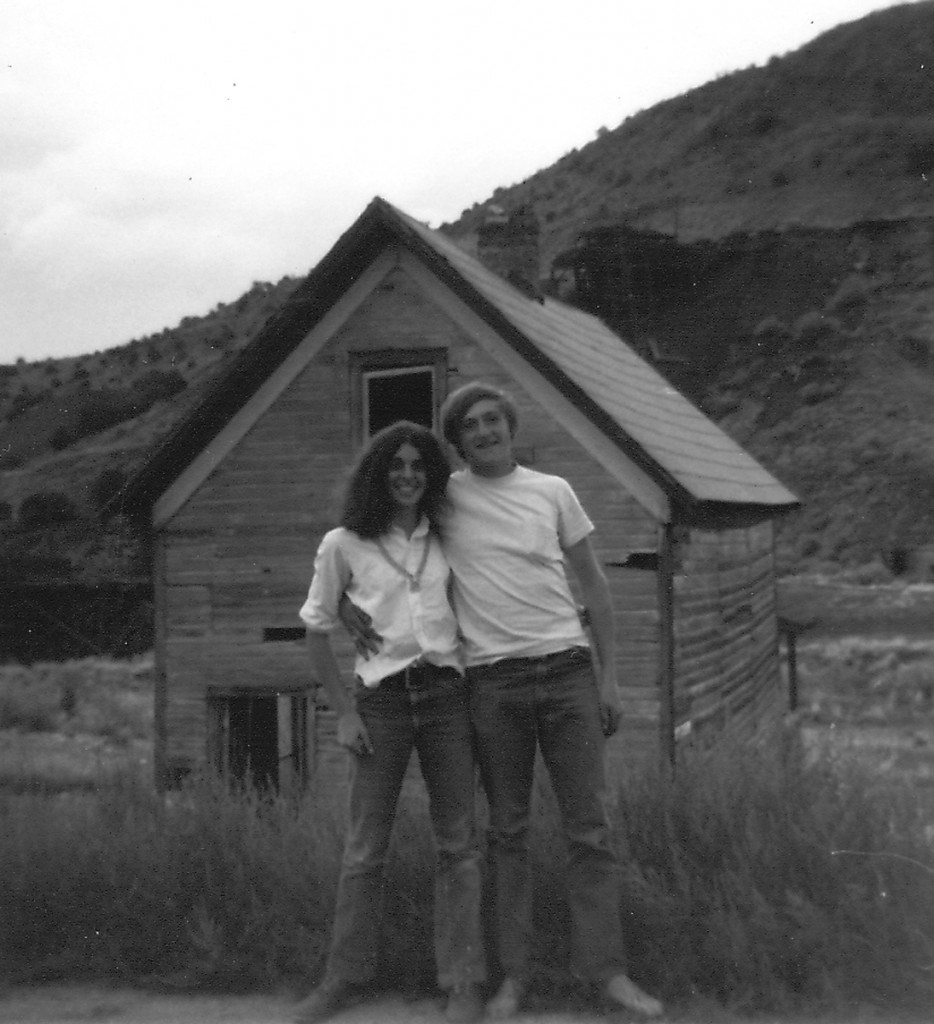

All told we’d been out for about eight hours. Photographing — or for that matter doing scientific research — in the Dry Valleys is often very physical, and involves a lot of walking up and down hills while carrying a pack. And I still had a lingering cold the entire time, but was damned if that was going to stop me. Last week a woman who writes a travel blog called me up to interview me about the Antarctica trip. She asked about my formative travel experiences. This got me thinking about the aforementioned Camp Whippoorwill, where I was introduced to hiking and camping in the Adirondacks, and Crossroads America, a cross-country teen tour I took the summer I turned 16. I spent those nine weeks riding around the U.S. in a Ford Econoline van with nine boys and girls and two adult leaders whom I’d never met before the day we started out. All my belongings were in a duffel bag, we camped outdoors almost every night, and we all had to get along with kids at close quarters whom we might not otherwise have chosen as friends.

I’m grateful and maybe a little surprised to arrive at this age with the energy, physical conditioning, and the ability to tolerate a lack of creature comforts and to roll with the inevitable glitches that arise, but I think it goes back to those formative experiences: reaching the summit of an Adirondack peak on a day where you could see for miles, singing to keep our spirits up while we walked in plastic ponchos getting drenched with rain, campfire meals of tuna-rice-a-pea (open cans of tuna, rice, peas and cream of mushroom soup, and stir), picking up my ground cloth after sleeping in the open at the bottom of the Grand Canyon to find a little white scorpion had also spent the night there. Somewhere were planted the seeds of confidence, resilience and determination to push onward until you reach your destination that have never left me. I think my teenage self would have been happy to know that.