Tuesday I went out with Evan, one of the mountaineers on staff here, whose assignment for the day was to take me to any icebergs frozen in the sea ice that interested me and back to the ice cave in the Erebus Ice Tongue. We went in Gretel, the same Haagland tractor featured in my sea ice training blog post, so it was lot easier riding around than driving a snowmobile. Snowmobiles are fun, but they get somewhat less fun when you have to travel for an hour on one — your right hand gets tired from being on the throttle, and it’s obviously colder, too, though aside from inside the cave, it was a nice day with little wind. I photographed three icebergs that are frozen in the ice, so you can walk right up to and around them, certainly impossible when they’re floating because it’s too dangerous — a floating iceberg can flip unexpectedly. I’ll post those photos another time, because I haven’t really had time to go through them yet, but I’m certain I’ll get some 3D files from them. Also got to see Mt. Erebus with no clouds and little wind, so you could see a puff of smoke rising above it.

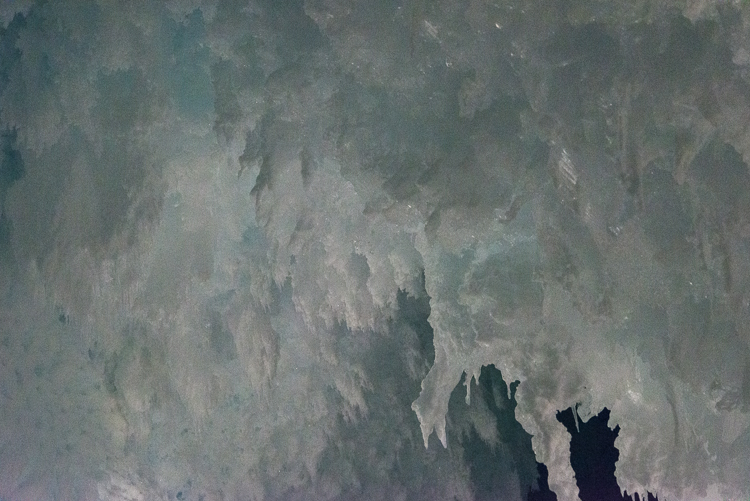

Then we went back to the ice cave, and this time, it was just me and him instead of a group of 15 people, and he brought a couple of good lights, which helped me get some better results. It also was a few hours earlier in the day, and it seemed to me there was more light coming through the small opening (very small — you have to crawl through it on your belly). I had learned from the first visit that the flash lit things too evenly. They were nice exposures, but you couldn’t see the depth. Even when I tried notching the flash down, it didn’t look so great. So, we experimented with having him point the lights he’d brought in different places to see what would work best for photography, and I discovered that indirect light worked the best — bouncing it off a wall, backlighting formations, or aiming it so the center of the beam was hidden behind a feature. Aiming the lights in that manner, we lit up some crystalline formations that I hadn’t even noticed the last time I was there, including some very large hexagonal crystals, an inch or more across! This is Evan’s first season here in Antarctica, but he leads winter mountaineering and backcountry ski camping trips in Idaho and Wyoming, and though he was familiar with hexagonal ice crystals he was astonished by the size of these.

Being inside the cave was literally being inside a walk-in freezer so I had to pause periodically to warm up my hands — my glove liners are usually pretty good for photographing but it was very cold in there after a while. Evan showed me some tricks that helped — swinging arms or pumping your hands up and down with your palms facing down. But after we’d been in there for a little over an hour, my fingers and toes had had enough, so it was time to go. But I left with some magical and strange images. They did remind me of some of the photographs I’ve made of cloud formations:

Amazingly wonderful adventure! Thanks for sharing in words and pictures. I’ve rarely seen anything so beautiful.

Thanks Elizabeth! Glad you’re enjoying it.

This is unbelievable Helen! Most impressive! What an exciting adventure!

There are so many similarities visually between these ice formations and clouds! This is such a wonderful blog.

Thanks Joel!

The indirect lighting photos are spectacular, Helen! I loved the Sports News commentary and the fun photos, too. Not so sure about the constant cold but what do I know?

…I’m such a wuss!

Admiring your adventuresome spirit from afar,

Linda

Hi Helen,

I was wondering if you had to be a scientist or someone who has a professional interest in the area to visit the Erebus ice tongue and caves. I am neither, just someone who is really interested in exploring wild places. Recently, I went on a weeklong trip through Son Doong in Viet Nam. I imagine the skills required are totally different, but just wanted to name drop in case it makes a difference.

The ice tongue cave seems to only be open for a relatively brief period of time (a few weeks) when the sea ice is passable for travel and after the mountaineers on station have gone in there and ascertained that it’s safe. The McMurdo Station Recreation Dept. ran a few trips open by lottery to people working here. Since I was here as a grantee of the Antarctic Artists and Writers Program and my project involved documenting ice formations a separate trip was scheduled for me to go with a mountaineer. It’s not a large cave and being in there is like being in a walk-in freezer; we were in there for between 60 and 90 minutes and by then my hands and feet had enough. The caves up on Mt. Erebus itself are much less accessible — only open to researchers and US Antarctic Program staff who are supporting their work such as mountaineers. That’s a much more complex undertaking, involving completing some additional field skills and safety trainings before going there, then being helicoptered up there (which can be iffy — many days the flights are cancelled due to weather), and acclimating to the altitude. My roommate for the first few weeks here was a volcanologist who spent 3 weeks on Erebus with a team from the University of New Mexico measuring gases in the caves. Given the complex and expensive logistics I can’t imagine they’d send anyone up there who didn’t have a science-related reason.