Biologists who study the creatures that live on the ocean floor in McMurdo Sound do their work during the first part of the summer research season. That’s when the sea ice is strong enough to support the heavy tractors that tow the dive huts onto and off the ice. Huts on the sea ice are removed by mid-December, when air temperatures warm and cracks in the ice widen and deepen. In a previous blog post, I’ve already written about my stay at Sam Bowser’s field camp at New Harbor, which is across the sound from McMurdo at the edge of the Dry Valleys. Other scientists collect samples right by the base, from a dive hut set up on the sea ice that’s a short downhill walk from the Crary Lab and the helicopter pad.

Near the hut, a smaller hole is drilled in the ice and the Observation Tube is installed. Known around town as the “Ob Tube,” it’s basically an underwater manhole with windows, dating back to the days when the U.S. Navy ran McMurdo. Anyone living on the station is permitted to go to the station firehouse any time of day or night and pick up the key, as long as they are accompanied by at least one other person. I went with Shaun O’Boyle, the other Antarctic Artists and Writers Program participant at McMurdo while I was there, on the morning of November 27th, timing our visit for a morning when we knew biologist Gretchen Hofmann’s dive team would be working there.

A visit to the Ob tube is not for the claustrophobic. I’m not a large person, but climbing down the tube via metal handholds while wearing a down parka didn’t leave much room to maneuver. You descend the last few feet via a rope ladder, which is visible in the background of my inadvertent selfie below. Standing at the bottom, you are surrounded by windows and looking up at crystal chandeliers of sea ice. Schools of tiny fish scoot past.

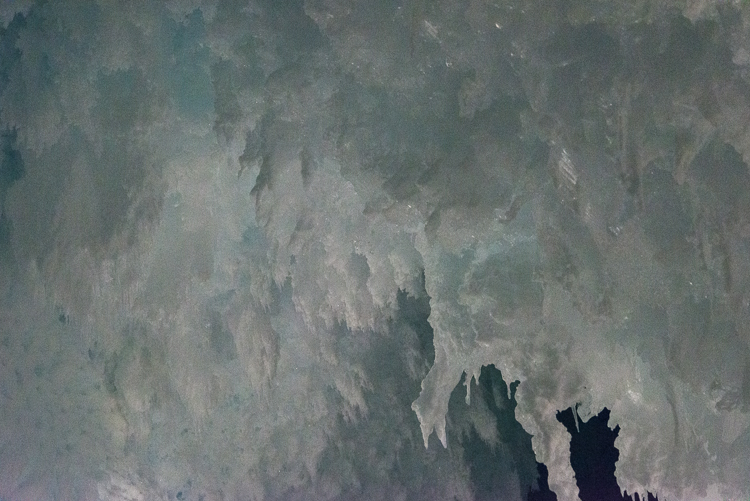

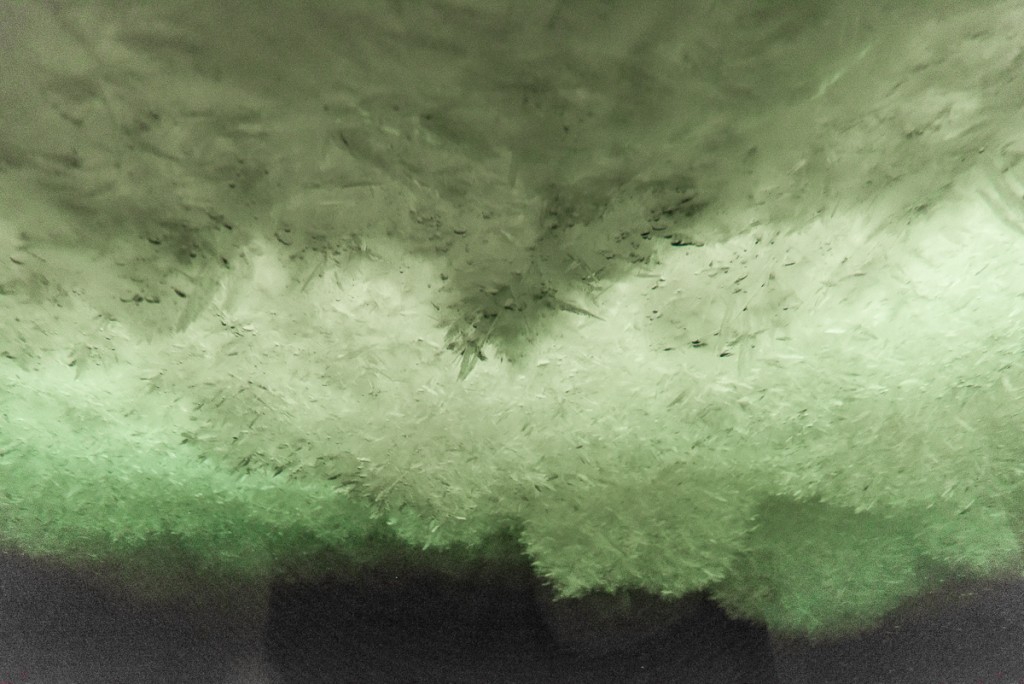

The Ob Tube provides a unique view of the underside of the sea ice, which is covered with mounds of platelet ice, clusters of thin, irregularly shaped slivers of ice, each a few millimeters thick and around one to four inches in diameter, that attach together at apparently random angles. Composed of 80% seawater and 20% fresh water, platelet ice is a peculiarly polar phenomenon that Encyclopaedia Britannica’s sea ice article calls “perhaps the most exotic form of sea ice besides marine ice.” A scientific paper based on research at McMurdo explains that these “semi-consolidated” layers of ice can be anywhere from a few inches to several meters thick and in Antarctica are “commonly observed beneath sea ice in regions adjacent to floating ice shelves.” Located not far from the ice shelf/sea ice border, the Ob Tube is perfectly situated to observe platelet ice.

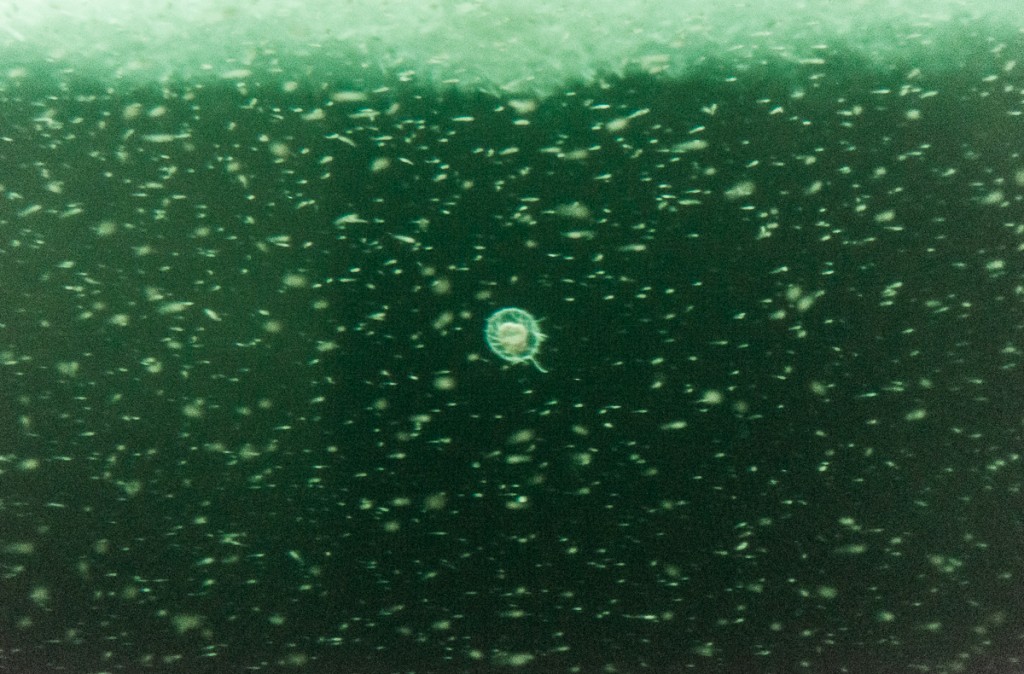

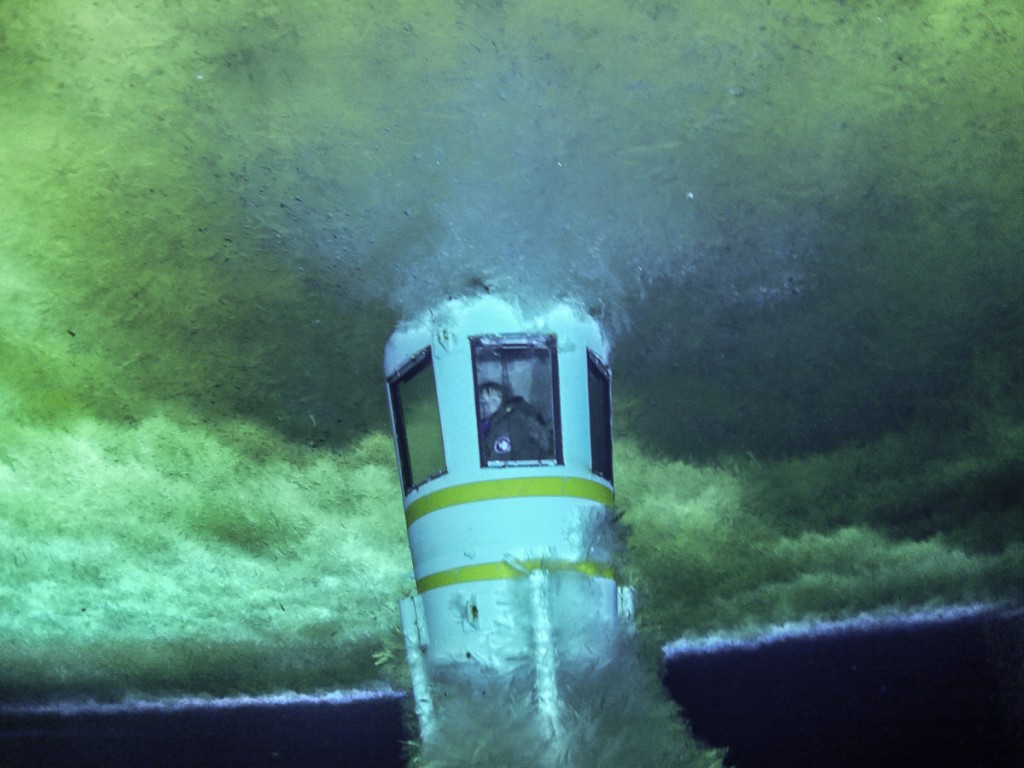

Gretchen Hofmann is based at the University of California Santa Barbara and is studying the impact of ocean acidification on the Antarctic pteropod and the Antarctic sea urchin. (Read more about her research on the Hofmann lab page.) Umi, a doctoral student and member of her dive team, swam up to the Ob Tube and helpfully wiped the frostiness off the outside of the windows with his gloves, which did making it easier to see out!:

A pulsing, glowing form the size of a dinner plate drifted past — a jellyfish:

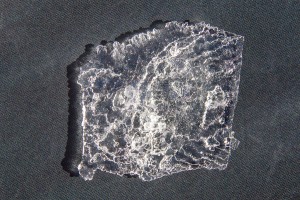

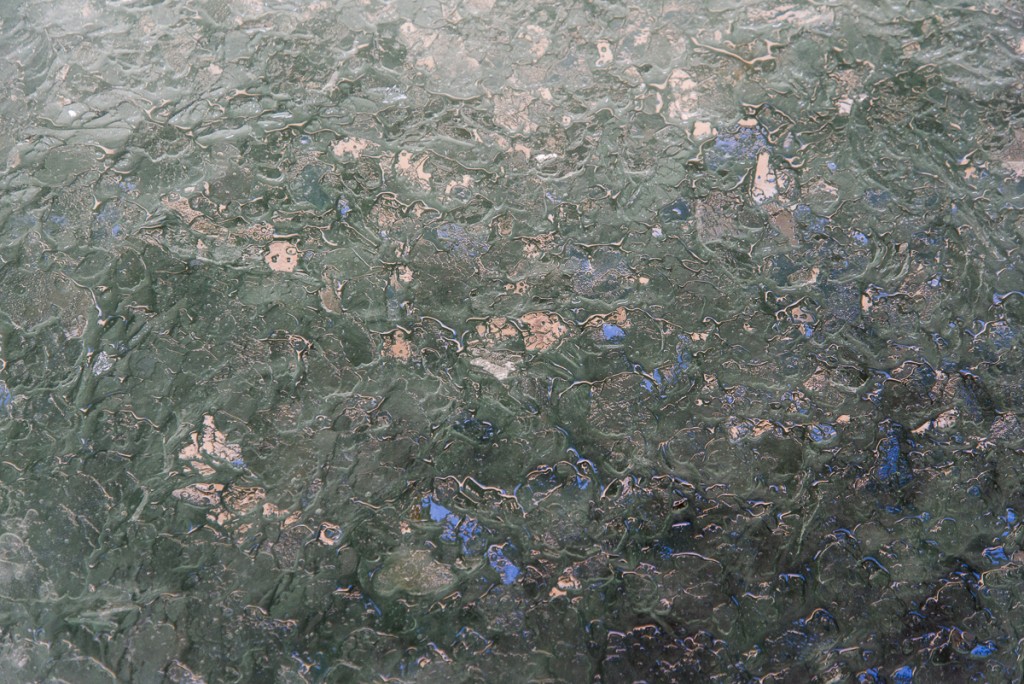

It’s a good thing Shaun and I got to the Ob Tube when we did, because a few days later, it was decided that it was time to pull it out and haul the dive hut back to dry land. I went back to dive area on December 5th, when Gretchen’s team was making their last dive. Steve Rupp, one of the two dive supervisors on staff at McMurdo each season, offered to take some photos of the outside of the Ob Tube for me, and to bring up some platelet ice for me to photograph up close. Elaine, my logistics coordinator, came along to help me. The plan was to scatter the platelets on some pieces of discarded tent fabric I’d borrowed from the McMurdo Craft Room as a backdrop, but periodic gusts of wind over 25 mph didn’t make that easy. What you can’t see in this photo is Elaine, who is truly a good sport, comically sprawled on her stomach holding down the fabric with both arms, while I scattered handfuls of platelet ice from a plastic bucket and took pictures.

After the dive was finished, I went inside the dive hut, and Steve leaned over the edge of the dive hole, shining underwater lights to illuminate the surface of loose, floating platelets for me, and throw them into low relief. These are a few of the photos I took inside the hut:

During his dive, Steve took some photos of the outside of the Ob Tube for me, which give a diver’s-eye view:

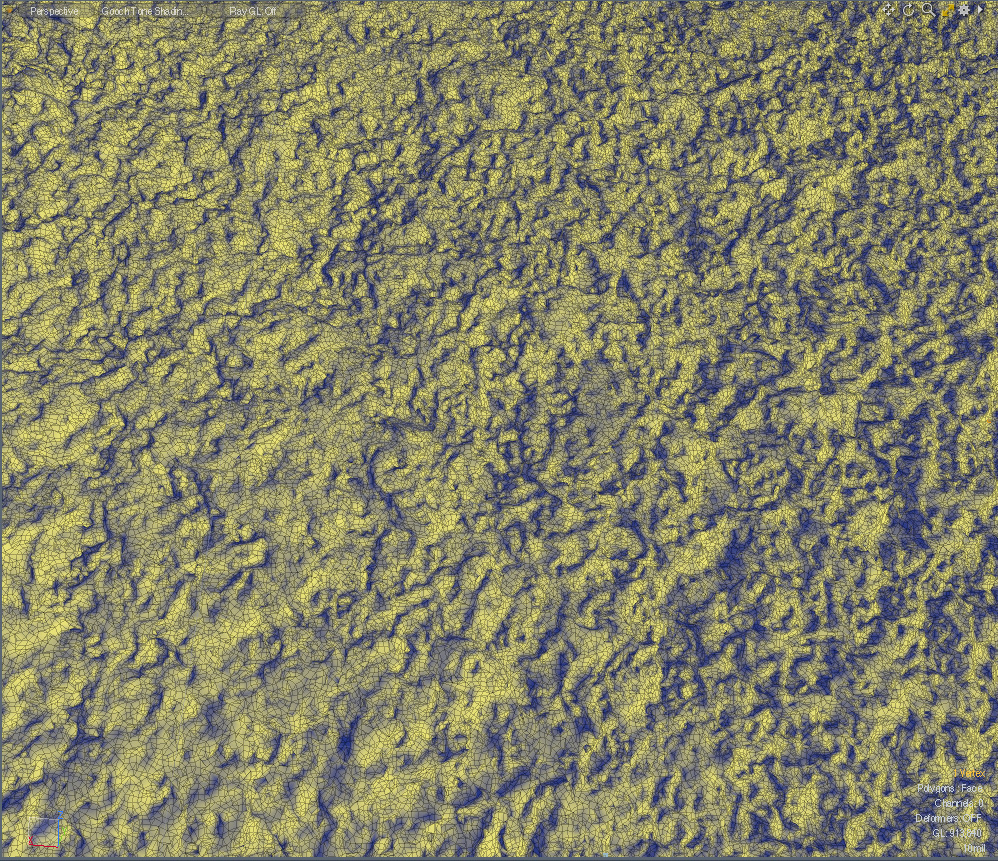

Steve tried to make a series of photos circling the outside of the Ob Tube for a 3D capture, but it proved too difficult for him to keep it in focus. However, I was able to take a series of photos of the surface of the platelet ice inside the dive hole while he held the lights underwater, and to make a 3D file from them. This is a screenshot of a detail of that file, rendered in yellow and blue shading to show the form:

Three days later, I happened to be in the Crary Lab Library overlooking McMurdo Sound when I saw workers loading the Ob Tube onto a truck in sections. The orange dive hut had also been put on a trailer to be towed to the spot where it spends the offseason: