The Lake Hoare field camp in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, where I spent five days, sits at the east end of the lake right next to the immense Canada Glacier. At the opposite end of the lake is the smaller Suess Glacier. When I first heard the name, it would not have surprised me if a glacier in Antarctica had been named for the children’s book author Dr. Seuss, given the odd landscape features that resemble some of his fanciful illustrations. But no, the 1910-13 British Antarctic expedition led by Robert F. Scott named it for Professor Eduard Suess (1831-1914), a prominent Austrian geologist and paleontologist who helped lay the basis for paleogeography and tectonics.

One day I hiked there accompanied by Mari, a young woman who normally worked at McMurdo in the field camp supply center, but was spending a couple of weeks at the Lake Hoare camp assisting camp manager Rae during a particularly busy period of the research season. There are many people in their twenties who work 10-hour shifts, six days a week at McMurdo during the austral summer as dining hall workers, supply staff, janitors, cargo loaders, etc., but their opportunities to travel beyond the base are limited. So Mari was thrilled to be in the Dry Valleys and enthusiastic about hiking to the Suess. We followed a path of sorts that had evolved from the walks of other researchers, which wound around the perimeter of the rocky north shore of the lake (on the right in the photo above).

After about an hour, we came across a mummified seal. Positioned on its belly rather than laying on its side made it look curiously animated, as if it was in the process of clambering out of the water. The mummified seals strewn throughout the Dry Valleys are an enduring mystery, and one I plan to write more about in a future blog post. Suffice to say, the icy climate and lack of organisms to break down dead animals keeps them in a state of preservation such that it’s difficult to know if that seal has been there a few years or a few hundred.

As we continued following the lake’s shoreline, we soon reached a very tall gravel hill that blocked our view of the glacier. Mari climbed to the top to scout the best route around it (remarkably quickly, too — it’s hard to get a footing on steep, loose gravel). As you can see in the photo at left, a stream of water was running downhill off the glacier into the lake. Mari had determined there was no shortcut to the glacier from where we were so we continued around the lake side of the hill.

From the Lake Hoare side, the Suess glacier is not nearly as impressive as the Canada Glacier in size or height. This panorama made from three negatives is pretty much what you see as you approach from the lake:

Walk around to the left of it and you can look uphill to see it flowing from the crest of the hill on the right:

But the really good stuff was just around the corner. The Suess flows down one steep hill and comes to rest where another steep hill meets it, forming a narrow passage called a defile. Once you enter the defile, you encounter another side of the Suess, a towering wall of glistening scalloped ice. It glowed with a peachy color reflected off the gravel hill:

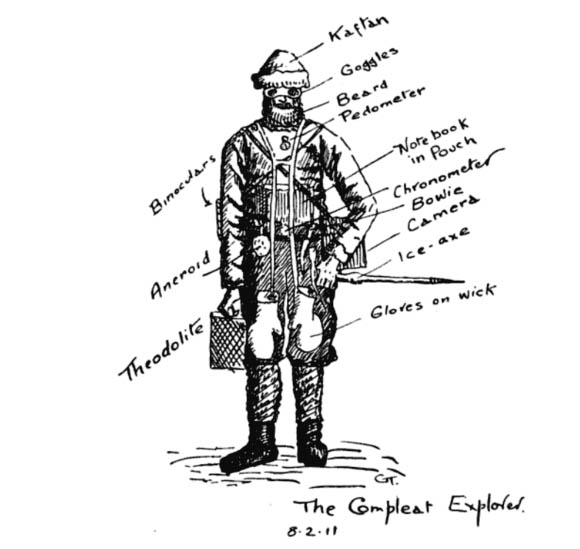

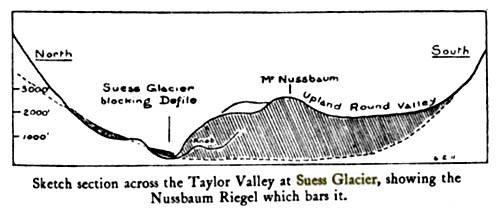

One of Scott’s party in the 1910-13 expedition, the geologist Griffith Taylor, described the discovery of the Suess in his 1916 book With Scott: The Silver Lining (you can find the section referred to here on Google Books). The title implies a motivation to spotlight the expedition’s accomplishments and successes, which had been to some degree overshadowed by its sad ending, when Scott and four of his men died on their way back from the South Pole. The following year, World War I broke out and was still raging when the book was published. As the book’s editor, Leonard Huxley, put it in the Introduction, “It is for Mr. Griffith Taylor to tell of the daily life of that company from within, to tell in careless detail its lighthearted cheerfulness lining solid effort, which the cloud of English earnestness so constantly turns out upon the night.” The section on the journey through what is now known as the Taylor Valley exudes the joy of discovery and is illustrated with Taylor’s charming drawings, including a humorous depiction of “The Compleat Explorer” wearing the state-of-the-art cold weather gear for 1911. (This includes “Beard,” which continues to be a popular male accessory in Antarctica. Once somebody said, “You know who I mean? The tall guy with the beard,” and the rest of us started laughing since that did not narrow it down at all.) At any rate, I’m guessing the Dry Valleys were associated with particularly fond memories for Taylor, because along the way Scott informed him he was naming the magnificent Taylor Glacier after him! Taylor’s book also includes his sketch of the Suess:

Taylor and company approached the Suess from the west, i.e. the opposite direction we took. His description remains apt today: “a face of ice forty feet high; but just where it butted into the steep south slope of the defile, there was a narrow gap where thaw-ice had filled in the interspaces between the cliff debris.” Mari and I put on crampons (velcro sandals with spikes on the soles) over our boots to walk on the icy passage where it narrowed to the width of a typical sidewalk.

We walked alongside a wall of ice with such hard, polished surfaces that it looked like it had been cast from a mold:

We also encountered the most impressive frozen waterfall I saw anywhere in Antarctica:

I was fascinated by the large rocks protruding from the icy wall that had apparently been swept up by the slow-moving glacier long ago. You see a couple of them in the photos of the waterfall above. The one below had to weigh several hundred pounds, and yet was somehow securely frozen in place in its icy niche:

Toward the end of the defile, where the narrow space opened up and the glacier height tapered off, another frozen waterfall had formed an ice stalactite and stalagmite:

Once out of the defile, the Suess presents yet another aspect, a frieze of rounded shapes:

We reached the end of the defile, and looked down at the small blue lake on the other side (below). It was 5 p.m., we’d been out for four hours and decided to go back to the camp, figuring we’d be there in 90 minutes, just time for dinner. That was the time we decided to take a direct route back across the lake ice which turned out to be, ah, no shortcut at all for us lake ice rookies. If you haven’t read that story, you can find it here. Long story short, we made it back, albeit almost three hours later with wet socks. It was unnerving while we were in the middle of it, but funny once it was over: silver lining!