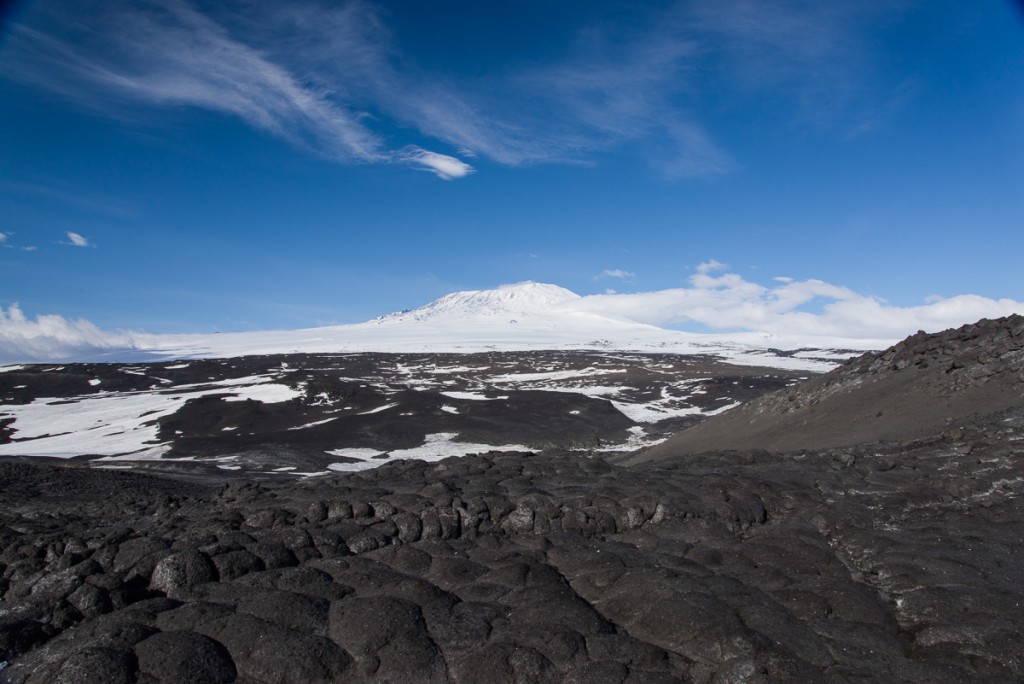

I can’t believe my luck. I mean, really. December 13th was my last full day at Cape Royds. It was overcast and the coldest day since I’d been at Royds and I had to keep stopping to warm up my hands. Not to sound melodramatic or anything, but I also had a cold and wasn’t feeling 100 percent. But I went out for a couple of afternoon walks with my camera and tripod anyway — one in the direction of the volcanic landscape, then after a pit stop at the field camp tent to warm up, one to the penguin colony. I have been told by the research team here that this is the time of year they typically see the first chicks. Nobody saw them yesterday, but Katie thought she heard a faint peeping and that there might have been some pecking their way out of their shells. Since I knew I would be getting picked up late morning the next day, I knew this would be my last chance to see chicks and I was on the alert for sounds. It started getting windy and I thought I heard something a couple of times but when I went over to investigate didn’t see anything. I wasn’t sure if it was my camera bag strap squeaking in the wind, which it does sometimes. After watching a colony that sounded like the direction it was coming from, I did catch a glimpse of an egg with a hole in it when a penguin stood up briefly and then settled back on top of it. But after waiting several minutes in the cold, I decided it wasn’t happening, my fingers were frozen and started walking in the direction of the path to the campsite. As I passed the neighboring subcolony, I heard an unmistakable peeping sound, looked to my left and saw this scene. It only lasted about 2 minutes — I took a few stills, turned on the video, and watched the penguin feed the chick and settle back down on it. You can see the video on YouTube.

Mostly what I saw while I was here were behaviors related to nesting. All the penguins who will breed this year have paired up, created little stone nests in their subcolony groups, and laid the eggs. The male does most of the nest-building, but once the female lays the eggs, they trade places sitting on the eggs. One goes down to the water to forage for food while the other sits on the eggs. When the foraging penguin returns, they great each other with a little dance where they swoop their necks up and down in unison and call out loudly. Then they switch places and the other parent goes off to feed.

I was hanging out on the bluff overlooking the water watching the penguins form little groups to go in the water. They just go down there and join with others who happen to be on their way, and walk more or less single file.

They’re fast swimmers and sometimes leap in and out of the water like a dolphin. I fired away with my camera and got some shots of wet, fast moving penguins that make them look like rubber dolls:

The pack ice floated at a good clip. Every day it looked different. On the 12th this iceberg showed up:

I tracked a penguin with my camera as he ran up a steep hill with a rock in his beak, which he presented to his mate in the subcolony at the top of the hill. There was an enthusiastic greeting between them. The landscape is rocky, he’s carrying a rock and something about the whole triumphant climb reminded me of the scene in the movie “Rocky” where Sylvester Stallone runs to the top of the long flight of steps at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. So I titled the video “Rocky.” Watch it on YouTube.

Young penguins three to five years old play at nest building, picking up stones and dropping them in a pile. Sometimes they even pair up, and do the whole greeting and changing places routine, but they are too young to breed and don’t lay eggs. Sometimes they make a nuisance of themselves and other penguins chase them away. I saw one in that situation running away who stumbled and slid about 8 feet down a slope on its belly.

The only predator the penguins have to watch out for at Cape Royds, aside from orcas in the water, are skuas, who look for an opportune moment to steal eggs. I saw skuas swoop down and harass the penguins numerous times, but most of the time, the penguins are onto them, and squawk and lean toward them menacingly. The skuas may stand there for a while, but once they know they can’t catch the penguins unaware they tend to fly off.

The penguins are unconcerned about the presence of people, however. Sometimes when I was standing in one place for a while, one or two would wander over to check me out. At one point I suddenly looked down to find I had company:

While I was there, Katie was making rounds every other day to check on the banded birds, making notes on the which ones were nesting and how many eggs they had. She has found that although the colony population hasn’t changed since last year, there are fewer nests and fewer eggs. Some nests were created but abandoned. Some pairs made nests but didn’t produce eggs and are just “playing house” as Katie put it. The scientists don’t know the cause of the lack of breeders, but one hypothesis is that something happened during the wintering over period that is making them struggle now.

The colony at Royds took a major hit when an immense iceberg named B-15 broke off the Ross Ice Shelf and essentially iced in a huge area of McMurdo Sound year round, preventing the sea ice from breaking up in the Antarctic summer. After it broke up in 2005, the colony began to slowly recover, but it has still not achieved its original size, even though there should be enough krill and silverfish for them to eat. You can see that when you look at an overview of the colony and see all the empty spaces that are tan in color where penguins used to nest. More research is needed to understand what is happening in the wintering over period and to look at some of the environmental variables that could be affecting their ability to survive and breed.