Sam Bowser and his team of five other people at New Harbor camp are getting ready to wrap up their season after almost 7 weeks on the ice. So what occupied them all that time you might ask? While I was there, they were kept busy all day and into the evening with tasks related to Sam’s research on one-celled marine organisms called foraminifera (which they call “forams” for short) as well as the daily chores of living at an Antarctic field camp.

Science-related tasks include diving beneath the sea ice to collect samples of forams from the upper centimeter of mud on the ocean floor, sieving the samples to find the forams, and then sorting them beneath a microscope into the different types they find there. When camp is closed up, they bring the specimens back to McMurdo where some are preserved and others are prepared to be shipped back live to the lab in Albany, NY, where Sam and two of the team members, Mike and Amanda work. Amanda worked with Laura and Sam in the lab, sorting specimens. They sometimes also note and take a look at other creatures that turn up in the collection bucket, such as scallops. Like a lot of ocean creatures in Antarctica, such as sea spiders, Antarctic forams are larger than elsewhere in the world, which is a major advantage if you want to study a one-celled organism. Amazingly enough, you don’t even need a microscope to see them, once they’re sorted. Some of them look like little white beads, and are rounded and smooth. Others, and these are the ones Sam’s particularly interested in, secrete an adhesive with which they manage to glue together grains of sand to form little shells for themselves — a remarkable enough feat, but they do this in icy ocean water. (That’s what I mean by “tiny stonemasons of the deep.”) Sam is working to figure out how. Laura laid some out for me to look at in a tray, picking them up with tweezers (they’re also surprisingly sturdy and don’t break when handled carefully). Different species can be identified by their characteristic shells — some only use very fine grains of sand, some use larger ones, some are rounded, some are branch-shaped, and one is sort of star-shaped. As you can see in these photos, you don’t need any special magnification to see them, although the microscope helps to see the structures in detail — above is a photo I took of the tray (click to enlarge all the smaller photos) and below is a close-up.

Camp chores include fixing meals and cleaning up, waste disposal, getting chunks of sea ice to melt for washing hands and dishes (bleach solution is added to disinfect it for that purpose), and meeting the helicopters that periodically deliver supplies and take away waste, because no waste, including used washing water, pee, poop, or trash that can or cannot be recycled is left anywhere in Antarctica. (That goes for McMurdo, too, with the exception that the station has a water treatment plant so the water and sewage isn’t shipped off site, but all other waste is ultimately sent off in container ships to California for processing.) All seven of us slept, cooked and ate in a pair of connected Jamesway huts. There is a separate structure that houses the outhouse on one side and the lab on the other. There is also a Jamesway on the ice that serves as the dive hut (it will be brought ashore when they close up the camp) and has all the diving equipment, as well as a hole in the floor where they can dive. But sometimes the divers travel to other dive holes they made elsewhere in the sea ice. I was surprised to hear that the ocean depth at the dive hut is 80 feet, because you can walk there in about 10 minutes from the shore. I also watched them dive from a hole they called the “tile hole” that is over water 40 feet in depth and those are the pictures you see here.

If the weather is “Condition 3” (i.e. good enough weather to safely go outdoors) the divers typically make two dives a day to collect samples. There were three divers this season who took turns diving, once in the morning and once in the afternoon. Two dive and one stays above ground to set up and help them in and out of the water. On my last day at the camp, Sam wanted some more samples from the area near what they referred to as the “tile hole,” so they brought their gear over the sea ice from the dive hut via sleds attached to snowmobiles. I walked over there along the shoreline and then carefully shuffled across the sea ice to the dive hole because there are lots of cracks you don’t want to get your foot stuck in, ice is slippery, and the surface is tilted and uneven in places. That day, Henry stood watch and Mike and Paul dove.

Now, I snorkeled once in a cenote (underground cavern) in the Riviera Maya in Mexico where we wore wet suits because the water temperature was in the 60s. And that was fun. But putting on a dry suit and entering 28.5 degree F water under a few meters of ice when the air temperature is in the upper teens sounds daunting, like the kind of thing you do because you have to as part of your job, not because you want to. But these guys live for it. I saw them come up from two different dives, and both times the divers came out saying, “That was great! I didn’t want to get out!” The dive durations are limited by the amount of air the tanks hold. After they came up and Henry helped them get the tanks off their backs, they hung out for a couple of minutes in the dive hole, as if they were sitting in a hot tub, and chatted about the octopus they’d seen in the same spot it had been several days ago. “It’s alive, it waved one tentacle,” one of them said.

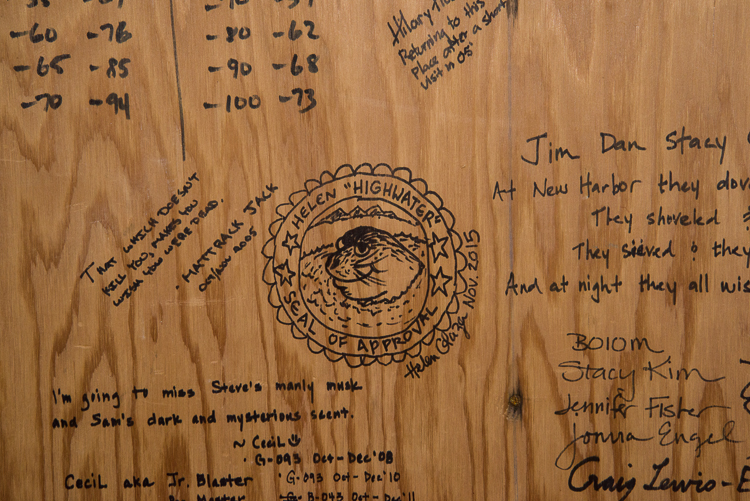

Laura has been posting photos of the camp’s activities all season on Facebook under their National Science Foundation as “Bravo! 043” (Bravo 043 being their radio handle when they communicate with the base camp.) See them here.